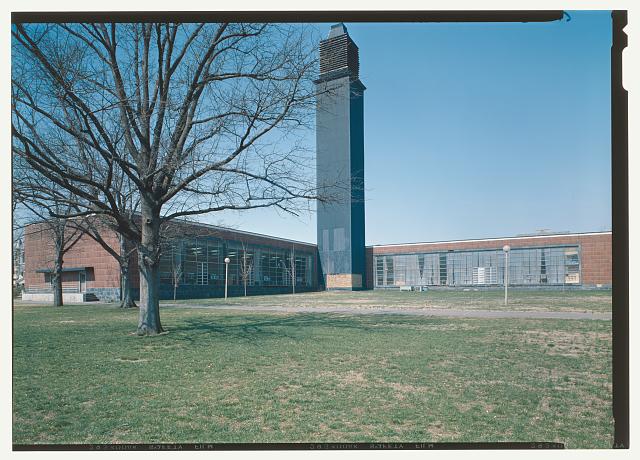

Image: McCord Engineering Building at Tennessee State University (TSU) in Nashville, Tennessee. George Francis-Kelly

McCord Engineering Building

The McCord Engineering Building at Tennessee State University (TSU) in Nashville, Tennessee, is a three-story brick and stone structure built in 1948. It was designed by McKissack & McKissack, one of the United States’ largest Black-owned architectural firms founded by brothers Moses and Calvin McKissack in 1921 as Tennessee’s first registered African American architects. The building was named after Governor Jim Nance McCord, who signed an executive order providing funds for the Engineering School in 1947. At a total cost of $800,000, it was by far the most expensive campus structure at the time of its erection.

The McCord building and Engineering School at TSU was part of a broader expansion at the college, the result of years of political wrangling. Faced with a 1939 legal case brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People which sought to integrate the entirely white University of Tennessee, the state’s General Assembly passed a law in 1941 which promised to ‘provide educational training and instruction for Negro citizens of Tennessee equivalent to that provided at the University of Tennessee…for white citizens.’

This meant providing courses for Black students at TSU that were previously unavailable, including law, postgraduate qualifications, and engineering. After tentative efforts to offer engineering modules at the college in the mid-1940s, the level of student interest in these and other science courses far outstripped anticipated demand, and by 1947 white officials from the State Board of Education recognised the urgent need for a new building.

With an imposing stone entranceway accompanied by several engraved crests and modern glass doors, the building provides a good example of the ‘Classic Moderne’ style of Art Deco design typical of the McKissack firm and a popular choice for educational buildings both locally and nationally. The horizontal emphasis of the building provided greater space to build large and well-equipped laboratories than a taller and narrower structure, with laboratories a critical part of attempts to improve facilities on the campus. Accordingly, the building contained laboratories for electrical engineering, cement, soil, sand, physical, and hydraulic testing, a foundry, combustion engines, and a model laboratory for teacher-training as well as refrigeration equipment and air conditioning.

Taken within this context, the McCord building offers an excellent example of attempts at US campuses to improve structures and facilities to further orient higher education towards science, technology, and engineering at the onset of the Cold War. Moreover, it illustrates the racial politics at play in the design and construction of Historically Black College and University campuses, as Black educators insisted that their students also play a role in these new directions, while African American architects sought to make these imperatives a physical reality.

– George Francis-Kelly

Image: Belgian Friendship Building. Library of Congress

Belgian Friendship Building

The Belgian Friendship Building at Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia, was

the first example of European modernism to be erected on a university campus in the

United States. Its arrival in Richmond followed its use as the Belgian Pavilion at the

World’s Fair held in New York’s Flushing Meadows in 1939 and again in 1940. There it

displayed not only the art and products of Belgium, but also raw materials and art from

the Congo, which was at the time a Belgian colony. Its journey to a historically Black

university campus was overseen by John Malcus Ellison, its first African American

president. It was facilitated by the General Education Board, a Rockefeller family

philanthropy. The conversion of the tower, which in New York housed a carillon, into the

Robert Vann Memorial, named for the late editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, a VUU

alumnus, garnered further support from a who’s who of notable African Americans,

including Mary McLeod Bethune and Adam Clayton Powell, Senior, and provided the

city’s predominately Black Jackson Ward neighborhood with a riposte to the notorious

Confederate memorials on Monument Avenue. Despite its origins in exhibiting a

brutally colonial regime, in Richmond it provided facilities that supported African

American empowerment through academic achievement, sport, and the civil rights

movement. For a generation it housed the university library and science labs; Martin

Luther King spoke five times in the auditorium that doubles as the home of the Panthers

championship basketball teams. The building is the subject of a forthcoming book by

Kathleen James-Chakraborty, Katherine Kuenzli, and Bryan Clark Green, to be

published in 2025 by the University of Virginia Press.

– Kathleen James-Chakraborty

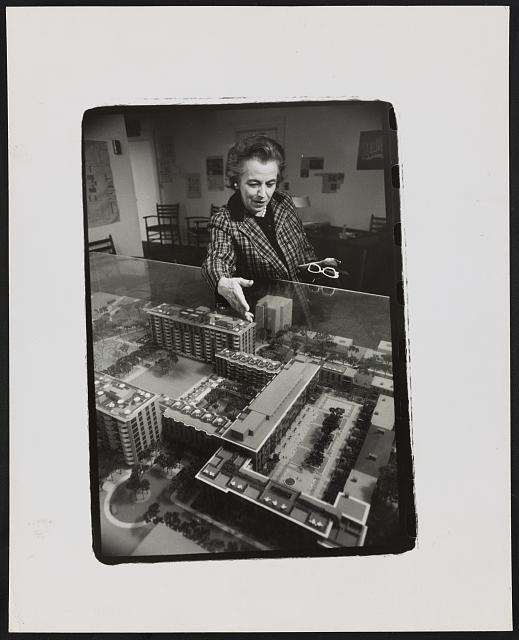

Image: Architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith presenting a model of her Harbour Square project for Southwest Washington, D.C.. Library of Congress

Ordinary Architecture and Extraordinary Woman

This book project explores the way in which five women, Ethel Power, Ethel Bailey Furman, Chloethiel Woodard Smith, Ruth Adler Schnee, and Denise Scott Brown, built careers in and around architecture that displayed a respect for the tastes of those women who could afford to make a choice about the appearance of the buildings they inhabited and the “ordinary” architecture they often preferred to that espoused by the upper echelons of the overwhelmingly masculine architectural profession. As editor of House Beautiful from 1922 to 1933 and a contributor for several years afterwards, Power shaped the reception of the International Style in the United States as just one of several possibilities for those committed to distinctively American standards of comfort and convenience. Furman, despite the lack of a professional architecture degree, designed houses and churches that fulfilled the aspirations of African American Virginians for dignified housing and community institutions. Woodard Smith played a major role in shaping postwar Washington, D.C., in addition to erecting housing from Boston to St. Louis that sought to provide attractive middle class alternatives to single family suburban dwellings. Adler Schnee’s fabric designs and the store she operated in partnership with her husband offer a window into the way in which modernism was made and marketed in a thriving second-tier metropolis. These case studies provide a next context in which to view Scott Brown’s championship of the “ugly and ordinary.” Based in Boston, Richmond, Washington, Detroit, and Philadelphia, these women were, with the exception of Scott Brown, located outside of what were perceived to be the centers of architectural innovation at the time, but this did not prevent them from having a demonstrable impact upon the way in which new architectural ideas were deployed across the entire country.

– Kathleen James-Chakraborty

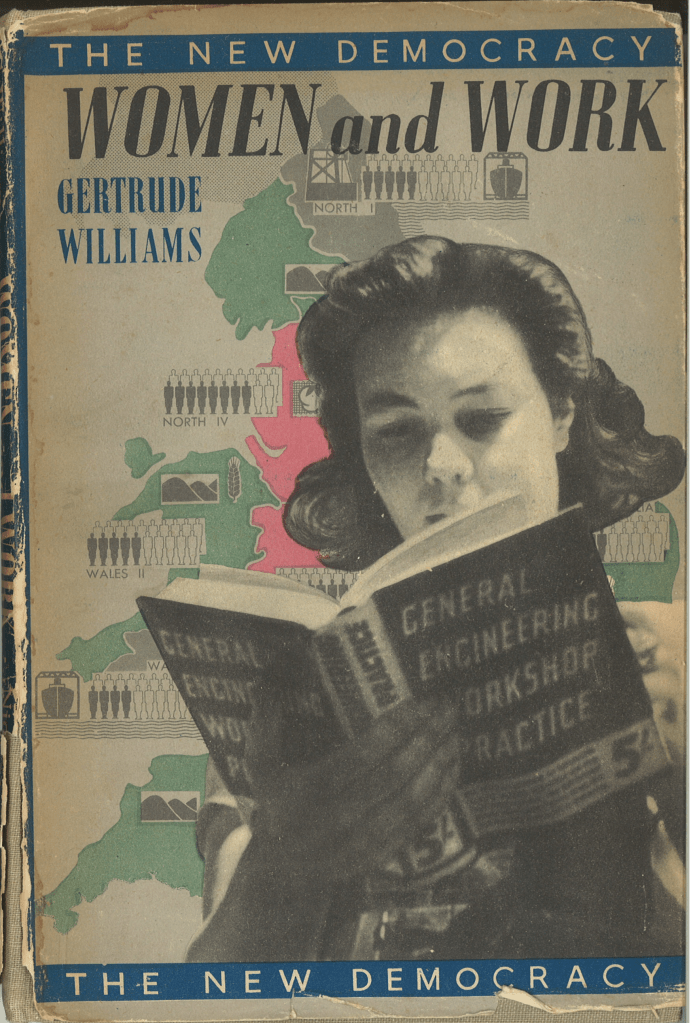

Image: Cover of Gertrude Williams, Women and Work (1945). An Isotype chart in the background displays the occupations of women in different regions of England and Wales.

Isotype and Women’s Movements

Originally known as the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics, the Isotype graphic system used straightforward visual elements to communicate complex information to non-specialist audiences. From its foundation, women were prominently involved in both operations and outputs, with charts often presenting socialist and feminist causes around equality of pay, maternal services and employment opportunities.

The Vienna Method was founded at the Social and Economic Museum by philosopher Otto Neurath in socialist-governed Vienna in 1925. A progressive figure, Neurath later announced in his rudimentary English: ‘I have always been for the womans’. The production of charts in Vienna depended on women including porcelain painter Elisabeth Buchmann, and architects Edith Matzalik, Rosa Weiser and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. The system’s chief ‘transformer’ – responsible for translating information into charts – was Marie Reidemeister, who later married Otto Neurath. The pair operated as joint directors as Isotype set course for Britain following Nazi pressure on the continent.

After the sudden death of Otto Neurath in 1945, Marie Neurath became the sole secretary and director of Isotype. In subsequent years, she laboured to introduce the system to West Africa, fulfilling long-term plans to use the symbols to communicate to illiterate audiences. Following colonial governance networks, Isotype undertook projects in British colonies in West Africa: Nigeria, Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast (Ghana). Despite the usage of Isotype to support feminist movements in socialist Vienna, this aspect proved malleable in Britain and West Africa, with Marie Neurath showing a willingness to adjust priorities. In Britain, Isotype charts were used to represent women’s required contributions to the war effort, drawing criticism from some feminists who sought women’s liberation on their own terms. In the Western Region of Nigeria, Marie Neurath searched for male teachers and students to apply the system, acknowledging local gender expectations. The case of Isotype demonstrates the complex external political and sociocultural circumstances that inform the production of design and its capacity to foster progress.

– Alborz Dianat

- Alb

Image: Sister Nesta, Becket Wing (right; 1970) forcefully meeting the historic Main School (left; 1896-98). Photo by Alborz Dianat.

Sister Nesta and Mayfield Convent

A Catholic girl’s school in Mayfield, Sussex, in England owes much of its built fabric to one of its own nuns: Sister Nesta Fitzgerald-Lombard (1916-2006). Over four decades, Sister Nesta transformed the site, renovating the historic fabric and designing new structures to accommodate rapid expansion.

Born in 1916, Nesta Fitzgerald-Lombard was among the first women to study architecture in Ireland after the inaugural school of architecture in the country opened at University College Dublin. However, only a small number of women from her cohort practised as architects after graduation. Prejudice and lower wages pushed most to marry swiftly for financial security, while married women were legally barred from many architectural commissions. Following an alternative path after graduating in 1938, Nesta Fitzgerald-Lombard journeyed to England. She entered the Society of the Holy Child Jesus and arrived at Mayfield convent soon after the Second World War. Far from preventing her pursuit of architectural practice, dedication to a religious life enabled Sister Nesta’s output. Relying on the voluntary contributions of a resident architect avoided insurmountable fees for the order. Trusted with renovations and new buildings at Mayfield, Sister Nesta aided the school’s merging with St-Leonards-on-Sea in 1953. The school established a house system to retain the intimate qualities of a small convent even after expansion. While the newly formed St Dunstan’s house was created in the existing Main School, the additional three proposed houses required construction. This led to Sister Nesta’s design of St Gabriel’s and St Michael’s, along with the renovation of a 16th century manor house to form St Raphael’s.

Operating with a limited budget, Sister Nesta’s architecture was unassuming, beyond occasional flourishes in decorative brickwork. Her projects met the historic fabric of the convent in uncompromising terms, with boarding needs outweighing sentimentality. Sister Nesta’s designs went far beyond providing accommodation, however. They also included renovation of the chapel as well as the creation of an administration wing, science laboratories, music school and a swimming pool. The extent of Sister Nesta’s output is astonishing for any architect, let alone one conducting their work alongside another occupation; Sister Nesta’s primary position was as Mayfield’s maths teacher and bursar. There are cases of women religious working on small construction projects collectively, from Carmelite nuns in Presteigne to Franciscan sisters in Surrey. But as a qualified architect leading such extensive projects over decades, the case of Sister Nesta is perhaps unique. Newspapers in England, Ireland and the United States highlighted the novelty of a nun-architect. Yet her international profile is dwarfed by the esteem still found for her locally.

– Alborz Dianat

- Alb